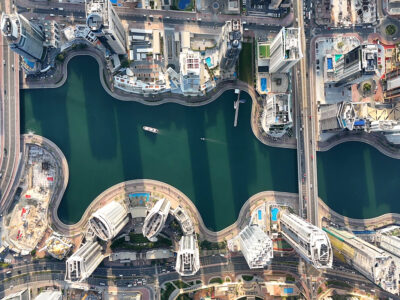

No fly zone|~|airbus-body.jpg|~||~|Nine months ago, Noel Forgeard was a happy man. Strolling around the Dubai Airshow, the boss of EADS – the company which has an 80% stake in aircraft manufacturer Airbus – could seemingly do no wrong. An Emirates Airline branded Airbus A380 had just buzzed around the show to the delight of visitors, and Forgeard was quick to put down any suggestion of problems ahead.

“It’s human nature that when something is doing well, you have to find something bad to say about it. People don’t like success stories,” he explained.

Nine months is a long time in the aviation business. Forgeard and his co-CEO Gustav Humbert are now history, having quit last week. Airbus is bracing itself for legal action from customers furious that the much talked about superjumbo has been delayed – delays which will wipe out US$2.5 billion of Airbus profits over the next four years. Not to mention the collapse in the value of EADS shares, or the mutterings of insider dealing following the mass sell off of EADS shares by Forgeard himself before the delays were announced.

“It’s not a question of what’s gone wrong. It’s a question of what hasn’t. From being the greatest event in aviation for decades, it’s all a bit embarrassing – and expensive – for everyone involved,” says aviation analyst Rajiv Gupta.

That’s an understatement. Emirates Airline has the biggest number of A380s on order – 45 in total – and has built into its future revenue streams the extra cash that will come from flying more passengers. Other big airlines, including Virgin Atlantic, Singapore Airlines and Qantas, also waiting to take delivery of the A380 planes, are now counting the cost. Many are thought to be considering what legal options they now have.

British lawyer Mark Atkins, who has dealt with airline lawsuits on behalf on passengers, says Airbus customers have a good case.

“From what we can see, it doesn’t look good for Airbus. Airlines that bought these planes haven’t just based future revenue and profit forecasts on taking delivery on time – it’s everything else that has gone with it. Some airports have practically been re-built just so the A380s can land there. There are lot of people who will want bills paying, and most of them will be sending the bills to Airbus,” says Atkins.

All this after what appeared to be a great year ahead for Forgeard in 2006. He was in ebullient mood as he greeted the world’s press amid the gold-leafed opulence of the Westin Hotel in central Paris in January. He stepped forward, clasped the lectern and smiled triumphantly.

The joint chief executive of EADS, the European Aeronautic Defence and Space Company, had good news. Airbus had taken orders for 1055 aircraft in 2005, outselling its great American rival, Boeing, for the fifth year running. It was a triumph for Europe’s most emblematic business, which politicians like to cite as a shining example of what can be achieved under Franco-German leadership.

But the best was still to come. Development of the long-haul A350 passenger jet was under way at a relatively low cost of US$5 billion. The A400M military transporter would soon be serving seven air forces. And above all, the flagship A380, the world’s biggest airliner with a capacity of up to 840 passengers and a catalogue price of US$292 million, would be in use by the end of year.

“I am counting on annual sales of US$50 billion in the medium term,” said the French chief executive, beaming.

Six months later, on June 14, he laid on another sumptuous reception, this time in the Rodin Museum in Paris. But his mood had changed. The smile had disappeared and, behind his square glasses, he looked worried. He left before the end.

The previous day, he had confessed, after weeks of denials, that his optimism had been gravely misplaced.

The A380, which had come to symbolise Airbus’s prowess after it was unveiled in January last year in the presence of Tony Blair, President Chirac and Gerhard Schroder, had hit turbulence. Production delays meant that only nine examples of the aircraft would be delivered in 2007, instead of 25, and only about 65 over the next two years, instead of 79. EADS would lose revenue totalling US$2.5billion as a result, Forgeard conceded.

Investors were appalled, not just because of the delays but because EADS and Airbus had repeatedly refused to admit anything was awry until then.

As EADS served mignardises to members of the Parisian elite at the Musee Rodin, its share price fell 26%, plunging the firm into the biggest crisis of its history.

It is a crisis with far-reaching political and diplomatic implications. Airbus was a rare, modern, European success story. But the story has veered into intrigue and turmoil. “The credibility of the company has been called profoundly into question,” said the stock brokers Aurel Level.

The credibility of its executives, most notably Noel Forgeard, suffered further damage when it emerged that they had exercised stock options in March, when EADS’s share price had been above EUR32. Noel Forgeard made a EUR2.5 million (US$3.2 million) profit; his three children made a total of EUR1.2 million (US$1.5 million); and four other EADS managers – Jean-Paul Gut, head of marketing and strategy, Francois Auque, head of the space division, Jussi Itavuori, head of human resources, and Stefan Zoller, head of the defence division – made EUR3.2 million (US$4.1 million) between them.

Accused of selling his shares after learning of the A380 delays, but before the news was made public – in other words, of insider dealing – Noel Forgeard defended himself vigorously. “Did we respect the rules? Yes. It was completely transparent,” he said, describing the timetable as a “piece of bad luck”.

The bad luck hit EADS’s two main shareholders, the French media and aerospace group, Lagardere and German carmaker, DaimlerChrysler.

Both had sold 7.5% holdings in April – before the price fall.

As stock market watchdogs in France and German announced inquiries, Lagardere’s chairman, Arnaud Lagardere, adopted the same line of defence as Forgeard.

He claimed EADS had lurched into such chaos that managers and shareholders had no inkling of the problems in its

main subsidiary.

“I have the choice between looking like someone dishonest and someone incompetent, who does not know what is going on in his factories,” he said. “The second version is right and I assume it.”

When a leading French industrialist proclaims himself inept, you know the malaise is deep. But what caused it?

The A380, launched in December 2000, was an unprecedented technological challenge – 73 metres long, 24.1 metres high, 79.80 metres from wing tip to wing tip and capable of flying 15,000km at a top speed of 1090kph.

The complexities were numerous and were compounded by the politically correct decision to use a production process supposed to mirror EADS’s European identity.

The main parts were to be made in Britain, France, Germany and Spain and then transported by sea, barge and road to

Airbus’s headquarters in Toulouse, southwest France.

As if this was not bad enough, Noel Forgeard – who headed Airbus from 1998 to 2005 when he moved up to EADS – offered airlines unparalleled leeway to modify the A380.

But each alteration meant more work for the 5500 engineers and 12 factories involved. They could not keep up. Last year Airbus announced a six-month delivery delay because parts were arriving unfinished in Toulouse.

The explanation for the second delay – the spark that led to this month’s crisis – is even more prosaic.

Workers have been unable to keep to the timetable for fitting the 500km of electric cables needed in each A380. Despite frantic attempts to speed up the process, the backlog has grown. Hence Airbus’s inability to deliver its flagship on time.

But if the only fault was electrical, traders would never have wiped US$6.25 billion off EADS’s stock market value.

They did so because the wires were a symptom of deeper failings – of incoherence and bad management.

These failings have their roots in Airbus’s origins. Born out of a political deal between London, Bonn and Paris in 1967, it was a hybrid industrial entity involving Britain’s BAe, France’s Aerospatiale, Germany’s Dasa and Spain’s Casa for almost three decades.

However, as Airbus took off, the structure became obsolete. In 2000 France and Germany moved to set up EADS, a holding company to control 80% of Airbus, with BAe, now BAE Systems, retaining the remaining 20%.

EADS was to operate like a normal business. Or almost. Although an improvement on what had gone before, it remained the child of political compromise between France and Germany.

There were to be two chairmen, one from each country, two chief executives, and equality between the German shareholder, DaimlerChrysler, which had a 30% stake, and its French counterparts, Lagardere and the Government, with 15% each.

It was a delicate balance and yet it worked at first. With Boeing in difficulty and airlines keen to promote competition between manufacturers, Airbus’s global market share rose from 15% in 1999 to more than 50% last year.

Noel Forgeard – a bright, rigorous, impatient man with the looks of a sixth-form prefect – should take much of the credit

for this. But in 2004 he upset the applecart. First, he used his connections with Chirac – for whom he used to work – to

replace EADS’s French chief executive, Philippe Camus.

Then he waged a campaign to prevent DaimlerChrysler appointing a second chief executive, seeking total control of EADS’s operational management for himself. He lost that battle, and now has to cohabit with the German Tom Enders.

The upshot has been to turn the group into a hornets nest. The French and Germans are at loggerheads, and the former are divided between Forgeard’s camp and that of Camus.

In a climate of suspicion and animosity, internal communication has broken down. With a legal battle with Boeing over subsidies looming, the hurriedly launched A350 facing such criticism that it will need a redesign at double the initial budget and BAE selling its 20% stake in Airbus, EADS must act swiftly if it is to regain investors’ confidence.

The dismissal of Noel Forgeard was urged by commentators but it would be only a first step.

The group needs to go further, streamlining its management structure, eliminating barriers and turning its back on politicians who see it as a diplomatic tool. But the omens are not good. The French Government’s first response to the crisis was to seek more power within EADS, not less – opening up a new front in the Franco-German struggle that has wiped the smile off Forgeard’s face.

Additional material from Adam Sage of The Times.||**||