Perhaps the most noble thing a journalist can do is bear witness in the very moments when power most wants silence.

There are nights when I close my laptop in Dubai and feel the crushing weight of privilege. The Wi-Fi is stable. The light doesn’t cut out mid-sentence. My colleagues and I at Arabian Business file stories late into the night, but always with the certainty that we will wake to another morning. And yet, just a few hundred miles away, Palestinian journalists in Gaza wake not to deadlines but to sirens and smoke.

I think of them constantly. I scroll through their names on casualty lists, see their faces in tribute posts. I wonder what it means for me – a journalist in absolute safety – to write about them while they die for the same craft. Is this survivor’s guilt? That sickening recognition that my safety is a lottery, that my byline lives while theirs are silenced.

But it feels like more than that. It is the weight of vicarious trauma, the way images, testimonies and fragments of violence seep into us, haunting even those who are far away. It is collective mourning, the grief of belonging to a profession bound together by duty, where every fallen colleague feels like a wound across borders. And it is a kind of moral injury – the ache of watching governments and institutions stay silent while our peers are deliberately targeted for doing what we all believe is perhaps the most noble calling: telling the truth.

Gaza’s journalists under attack

I know I am not alone in this. Journalists across the Middle East are feeling it too: watching from Beirut, Amman, Cairo, Doha, and Dubai, all of us united in horror. Gaza’s reporters may stand at the frontline, but the loss reverberates through every newsroom in the region, reminding us that we are one community – and that community is under attack.

It was the image no journalist could shake: a camera, toppled on its tripod, lens cracked and slick with blood. It was recovered in the rubble outside Gaza’s Nasser Hospital on 25 August, after an Israeli strike killed five journalists covering the scene. Freelance visual journalists Mariam Dagga and Moaz Abu Taha, who had contributed to the Associated Press and Reuters, lay among the dead. Cameraman Hussam al-Masri, a contractor for Reuters, was killed instantly. Photographer Hatem Khaled was badly wounded.

The photographs of that camera, its eye blood-red, ricocheted through newsrooms worldwide. For reporters, it was a visceral reminder of what it means to stand at the world’s edge, telling stories that others would prefer buried. “These journalists were present in their professional capacity, doing critical work bearing witness,” Reuters and AP wrote in a joint letter to Israeli officials. They demanded answers, questioning whether Israel was deliberately targeting live feeds to suppress information.

That blood-stained lens became emblematic of Gaza’s war on truth: every act of documentation now carries the risk of becoming evidence of its author’s own death.

The deadliest war for journalists

No modern conflict rivals the toll Israel’s war on Gaza has taken on the press.

According to the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ), nearly 200 journalists and media workers had been killed across Gaza, Israel, the West Bank and Lebanon by mid-August 2025 – the deadliest period for reporters since CPJ began tracking in 1992. Reporters Without Borders (RSF) cites “over 200” killed and has filed four war-crimes complaints at the International Criminal Court. The International Federation of Journalists (IFJ) puts the figure higher still, at 226 dead, with 64 killed in Gaza in 2024 alone – nearly half the global total for that year.

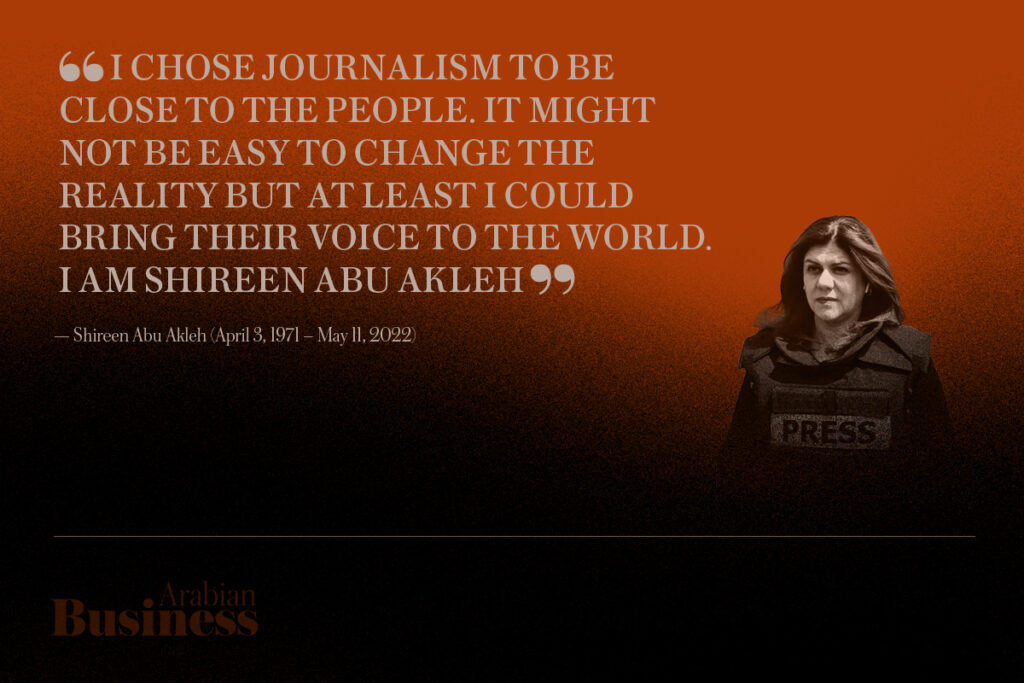

Local monitoring groups such as Shireen.ps – named for Al Jazeera journalist Shireen Abu Akleh, shot dead by Israeli forces in Jenin in 2022 – tally almost 270 journalists and media workers killed in Gaza since October 2023. On average, that is 13 every month.

The comparisons are staggering. Brown University’s Costs of War project concluded that more journalists have been killed in Gaza in under two years than were killed in the American Civil War, World Wars I and II, Korea, Vietnam, the Balkan wars and Afghanistan combined. “It is, quite simply, the worst ever conflict for reporters,” the study said.

“This scale is unprecedented and shocking. We can’t accept it!” Martin Roux, head of RSF’s crisis desk, told Arabian Business. “We can’t continue our work, as journalists, like business as usual. They were our colleagues and we have to do everything we can to stop this, by letting the world know. There is a clear intention of the Israeli army and authorities to impose a media blockade on the Gaza Strip. Along with the continued killing of Palestinian reporters, independent access of the international press inside Gaza has been constantly denied during the past 22 months.”

Gaza’s hunted storytellers

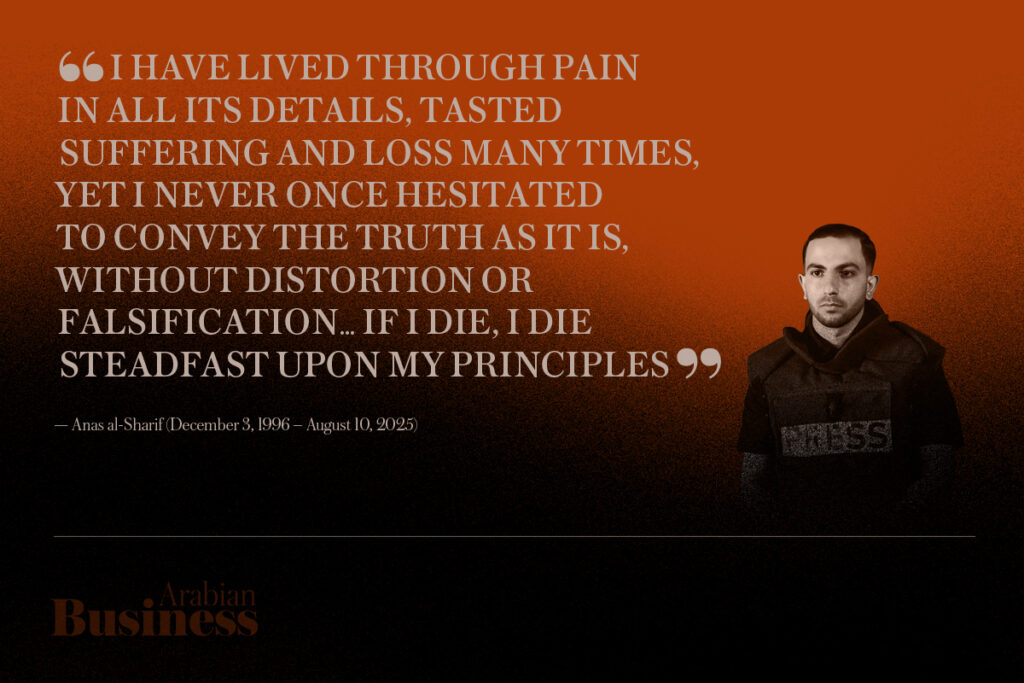

Among the dead is Anas al-Sharif, 28, a familiar face to millions of viewers of Al Jazeera Arabic. On 10 August 2025, he and five colleagues were killed when an Israeli airstrike hit their press tent outside Gaza City’s main hospital.

Days earlier, al-Sharif had handed the Palestinian Journalists’ Syndicate a letter describing the threats he and his family faced. His words read like a living will, a chronicle of persecution that doubles as testimony:

“Since the outbreak of the war in 2023, I have been subjected to dozens of threats by the Israeli occupation army.

The first of these threats was carried out through a direct targeting of my home and my family’s home, resulting in the martyrdom of my father.

I have received ongoing threats on a regular basis … in repeated attempts to halt my media coverage, silence my images, and interrupt the journalistic message I transmit from inside the Gaza Strip.

The threats were not limited to me personally; they also extended to my family members. My wife and children were subjected to direct threats, in an attempt to pressure me psychologically and professionally and discourage me from fulfilling my media and national duties. All of this is happening because my coverage of the crimes of the Israeli occupation harms them and damages their image in the world.”

When al-Sharif died under a banner reading “PRESS,” his prophecy was fulfilled.

His case is not isolated. Wael Dahdouh, Al Jazeera’s bureau chief in Gaza, lost his wife, son and daughter in a strike, then later his journalist son Hamza in January 2024. Cameraman Samer Abudaqa bled to death in December 2023 after medics were allegedly blocked from reaching him. Photojournalists Ismail al-Ghoul and Rami al-Rifi were incinerated in a marked press car in July 2024. At least 10 Al Jazeera journalists have been killed since the war began.

And yet, amid relentless death, some stories are still being written.

Shrouq Al Aila, a producer and researcher, continues to work inside Gaza despite carrying grief almost too heavy to bear. In October 2023, an Israeli airstrike on her home killed her husband, Roshdi Sarraj, co-founder of Ain Media. She and her infant daughter survived. Denied permission to leave Gaza even to accept a CPJ International Press Freedom Award, she now leads Ain Media herself. Between power cuts, displacement, and hunger, she continues documenting the war with her child by her side.

Her endurance is existential, proof that even after the destruction of her family, the story must go on.

Erasure and impunity

If Gaza has become a graveyard for reporters, it is also a black hole for information. Israel has barred international journalists from entering the territory for nearly two years, save for tightly controlled embeds. Meanwhile, censorship has tightened at home. In 2024, the Knesset passed a law allowing foreign broadcasters to be banned; Al Jazeera was shut down in Israel in May that year. The Israeli military censor banned 1,635 articles that year, the highest number in more than a decade.

In the West Bank, Palestinian journalists have been arrested in record numbers. CPJ’s 2023 prison census ranked Israel among the world’s worst jailers of journalists for the first time.

“Journalists must not be targeted,” said Budour Hassan, Amnesty International’s researcher on Israel and the Occupied Palestinian Territory. “Directly targeting and killing journalists amounts to a war crime under international law.”

Amnesty condemned what it called a “pattern of targeting journalists and photographers,” stressing that “no conflict in modern history has seen a higher number of journalists killed than in the context of Israel’s genocide against Palestinians in Gaza.”

Invisible wounds

Physical danger is only part of the story. For Gaza’s surviving journalists – and for many covering from afar – the psychological toll is profound.

“From a clinical perspective, what makes covering war zones uniquely traumatic is the dual role journalists are forced into: they are both witnesses and participants in the trauma,” said Dahlia Yamout, a clinical psychologist at Thrive Wellbeing Centre in Dubai. “The camera is on, the report must go out, and the duty to inform overrides the instinct to protect themselves. This creates an unbearable split… living through horror while masking it publicly.”

The long-term costs include intrusive memories, flashbacks, nightmares and survivor’s guilt. Many remain in a state of hyperarousal, easily startled, irritable, unable to concentrate. “Journalists often struggle to connect with everyday concerns or feel alienated from those who haven’t lived through war,” Yamout added. “These scars can make it difficult to sustain their careers.”

Some feel a deepened duty to keep reporting; others develop a heightened sense of humanity and gratitude for life’s simplest moments. This duality – between growth and burden – becomes part of their identity.

A call for justice

Legal frameworks exist. UN Security Council Resolution 2222, adopted in 2015, obliges states to protect journalists in conflict. Yet it remains unenforced in Gaza.

RSF is urging an emergency Council meeting. Amnesty calls for arms embargoes and sanctions. Press unions demand a new international convention on journalist safety – a Geneva Convention for reporters. Reuters and AP have joined that chorus, demanding transparency after their own contributors were killed at Nasser Hospital.

“These deaths demand urgent and transparent accountability,” they said in a joint letter.

Without accountability, the precedent is dire: if Gaza’s killings go unpunished, journalists everywhere become fair game.

Since October 2023, over 60,000 Palestinians have been killed as a result of the conflict, according to Gaza health authorities and UN agencies – around half women and children. Humanitarian organisations warn that rising malnutrition is becoming a severe crisis as aid remains largely blocked despite relief efforts led by countries such as the United Arab Emirates.

I think of Gaza’s reporters – waking to sirens, strapping on their vests, picking up their cameras. Some will not live to file tonight. Yet they step forward. Because truth matters. Because if they stop, the world will never know.

The blood-stained camera at Nasser Hospital still sits in my mind. A witness silenced, but also a reminder: the story itself endures. As long as we look, as long as we read their words and see through their lenses, the story lives.

This article first appeared as the cover story in the September issue of Arabian Business.